Sign, object, and concept

Pay attention, now we will be considering almost the same thing as in the previous section - the world (background), objects, names, categories. But from a different perspective, highlighting different boundaries of entities, different relationships, using similar (but sometimes new) words for completely different descriptions. Of course, after this, we will rebuild the bridges to the previous content, connect these explanations, and develop them further.

Looking at the same thing from different perspectives is one of the fundamental tools of systems thinking, which you will study in the future as part of our program. However, practicing the ability to determine within which method of description what you are reading or hearing was created - we will start right now.

So, in the context of familiarizing ourselves with semiotics (the theory of sign systems), we will discuss:

- How the ontology of this theory is structured (which entities are distinguished in it);

- How reference (referentiation) from signs to values is structured;

- Why we can call categories "objects of mental space", "ideas" or "meanings";

- How reference for physical objects differs from reference for objects of mental space.

When we think with the help of the tools of sign theory (inside our heads or on paper) about the world, we identify signs, objects, and ideas.

Sign (symbol) - this is a unit of meaningful communication, it is what we see, and what we understand as a reference to something else.

A word is a unit of natural language.

Hieroglyph - a unit of hieroglyphic writing.

Pictogram, icon - a unit of a pictographic system, a system of visual representations.

Shields, swords, and unicorns - units of heraldic language.

And so on.

A sign is by itself a physical object (individual) in terms of ontological modeling, which we familiarized ourselves with in the previous section.

The word "table" is printed with ink on a sheet of paper or displayed on the monitor screen with pixels, or written with magnetic domains on the disk of a computer, or carved on a stone slab, or conveyed to us in the form of a package of sound vibrations.

Non-text signs - even more material objects. A sword, a skull, or a black cat can be very clear signs of a purely material nature.

But this materiality of the sign is not important for us now, we will consider the word "table" as the sign "table", without specifying its material carrier. All instances of the word "table" in this sense "work" the same way, whether they are written on paper or carved in stone.

A sign is not a model! We use a model to make meaningful judgments about something else, while a sign is precisely a reference, a way to point out something. Signs and models are separated by our attention for different purposes, although sometimes they may coincide in the world as individuals, again an example of different considerations for the same thing.

Object (meaning, signified) - is the object to which the sign refers, to which the sign gives a name.

What objects of attention are -- we discussed in the previous section. There we introduced a distinction between physical objects and categories. The signified for a sign can be both a physical object (individual) and a category.

When you say “put it on the table in the kitchen” - you use the sign (word) “table” to refer to a specific table in your kitchen.

When you say “an office usually has a table” - you use the same sign to denote a category of physical objects.

All objects that are the meaning of a given sign are sometimes called the extension of that sign (such a term is accepted in semiotics, and this Latin root we have already encountered in ontologies and will encounter it again), emphasizing that all objects (even in possible or imaginary worlds) have an extension in space and time, you can (at least theoretically) “touch” them - touch, see, smell, or at least imagine these actions in your mind. If the signified itself is a category, the extension consists of all the physical objects that belong to it, but, following the conventions in ontologies, we would call it intension.

Note that combinations of elementary signs form compound signs, for example, whole phrases. Therefore, we can work with complex patterns or situations that are the meanings of these phrases, standing behind them.

Idea (concept, meaning, concept) - is the content, quality, set of features that constitute a commonality for all objects denoted by the sign. You can consider the idea (concept) as the abstract content of an object, or its generalized mental image.

When you hear or see the word “table” printed - there may not necessarily be a reference to a specific table in that communicative situation. But the word itself generates in you a generalized image, a set of visual or tactile experiences, summarizing your concept of a table. It is said that you have an “idea of a table” - an understanding of what a table looks like, whether it has one leg or four, is made of wood or metal, but there is such a concept, and you will recognize it when you see it.

Often it is said for brevity that the concept is the same as an image, but it is not entirely correct: the concept does not necessarily have to be “visible,” it is amodal, which means it does not contain information for the sensory organs, you cannot say that we see, touch, smell, or hear it. Information tied to sensory organs may appear when a specific person with a specific experience brings this concept to mind. Therefore, even though each of us has slightly different concepts, the vast majority of them are similar enough for us to be able to discuss them, and this facilitates communication between us (this is another perspective, from the standpoint of other theories, on the importance of the previously mentioned shared ontologies and models).

All objects corresponding to a concept are called the extension of the concept, they are also called its extension in semiotics.

It is also said that a concept (idea) for the concepts included in it is the content or intension, as it reflects the intentions, qualities, and properties for which it is created in minds and used in thinking.

As you can see, the “idea” in semiotics is a very close concept to the “category” from the beginning of the ontology. But categories themselves are objects to which signs refer. Therefore, every category as an object also has its own idea, meaning. An idea is something even more abstract, the most abstract thing you can imagine.

Perhaps some of the most general categories are indistinguishable from the ideas they embody, for example, the category “Individual physical object” introduced by us in the previous section. But this is already a philosophical (and, as always, debatable) question.

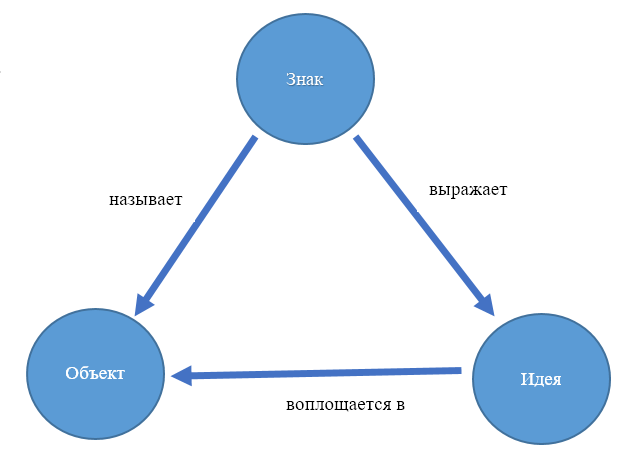

It is convenient to represent a sign, an object, and an idea by a diagram, sometimes called “Frege's Triangle” in honor of the logician, mathematician, and philosopher Gottlob Frege.

The relationships between the angles of this triangle can be described in different ways (relationships here look like triplets). The sign calls the object, denotes it, points to it. The sign expresses or personifies an idea. The idea embodies in the object, the object embodies the idea.

Frege's Triangle helps to memorize the entities distinguished in semiotics and their relationships. It shows how referentiation (the connection between a sign, an object, and an idea) works in principle, establishing dependencies between the angles of this triangle. But this diagram does not imply that a unique triplet of a sign, concept, and idea can always be found!

Words can have multiple meanings, the word “table” can mean a piece of furniture, or it could mean a government department in Russia before 1917. For some ideas (“beauty” or “justice”), there are numerous objects, items, and situations that can be considered embodiments of them, and all of them will have a vast array of other signs naming them much better and more precisely than just “beauty.”

Different signs can relate to the same objects and simultaneously express the ideas embodied by them!

The sign “table” (word) can, depending on the circumstances, refer to my kitchen table or a table in the store. And it can express the abstract “idea of a table.”

But the sign “Idea of a table” (a phrase of two words), which supposedly does not have an embodiment in the real world (hence it’s an “idea”!) still triggers in your imagination a memory (image, feeling) of my specific favorite work table, and this object can be placed in the corresponding corner of the triangle. Or maybe I don’t have a favorite work table, but I recall my favorite dining table. Well, in the third corner, there will still be the same idea of a table that is with the word “table.”

The sign “My favorite work table” (a phrase of four words) elicits in the imagination the feeling of the exact beloved work table, there are no questions there. What about the third angle? Philosophers debate about the third angle - is there a separate idea of my work table in an abstract world, or in this case, would the same idea of a table as with the word "table" be present again.

It looks complex and tangled? Any philosophical construct can be made bewilderingly intricate! But it is essential to understand why we introduce this construction.

We need, first of all, the ability to distinguish a sign (symbol), an object, and a concept, to differentiate what we are dealing with - with an object or a sign, with an object or an idea (which is not always so simple). And, secondly, the skill to select the most accurate sign for an object.

All these skills will be important for us in ontological modeling, an approach that slightly differs from the semiotic approach but is akin to it. But right now, having understood how signs work - we can delve further into the communication techniques that are carried out through signs.